HBIM Course: Reconstructing a Capuchin “Form-of-life”

Together with Fundação Oriente, our research has been exploring ways to safeguard and make accessible the tangible and intangible heritage of the 16th century Convent of Santa Maria da Arrábida, Portugal through digital documentation and storytelling. As part of the research, the project was integrated into the Master of Architecture program at Instituto Superior Técnico Lisboa during the 2022-2023 semester. The course, titled Historic Building Information Modelling (HBIM), is a project-based course using HBIM as a tool for heritage documentation and historic research.

A specific focus of this semester’s research, framed by the notion of a “form-of-life,” was to re-examine Franciscan ecological ideals for the present. The definition of a form-of-life was adopted from Agamben in The Highest Poverty: Monastic Rules and Form-of-Life (2011) who defines it as the indistinguishable mixture of conventual rules and daily habits. In our research this definition has been extended to include specific elements of conventual life in Arrábida including its architecture, myths, poetry, everyday objects, historic texts and ritual practices among other fragments.

In the summer of 2022, the project began with a digital documentation campaign involving laser scanning and aerial photogrammetry. In total, an area of approximately 4500 m2 of the old and new convent was recorded. The students made use of this data to construct millimeter precise models with an HBIM process to record the existing state of the buildings in the event of unexpected disaster and further degradation.

After learning basic modelling practices from point cloud data in Revit, students divided themselves freely into pre-defined themes related to the questions of our research. The students developed their work across three types of primary historic texts. These include the regulartory text Estatutos da Província de Santa Maria da Arrábida (1698), the chronical known as Espelho de Penitentes, e Chronicada Provincia de Santa Maria da Arrabida (1728) and a little known poetic text “Descrição da Arrábida” by Padre Inácio Monteiro (c.1685). These were also combined with more recent readings on the topic including the extensive descriptions in A Serra da Arrabida e o Seu Convento by Dulce Perestrello (1952). Although the themes were pre-defined, students played an active role in personalizing and shaping the research according to their own interests.

During the semester, students had the opportunity to visit the convent (about 48 km south of Lisbon), with guidance from members of Fundação Oriente. This was an important element of the research to fully comprehend the spiritual atmosphere of the place and to fill any knowledge gaps remaining from uncertainties in the digital surveying.

The topics explored by the students corresponded to spaces belonging to either the new or old convent. In each case the projects incorporated digital modelling with different kinds of digital storytelling. Below, brief snapshots of their projects are given:

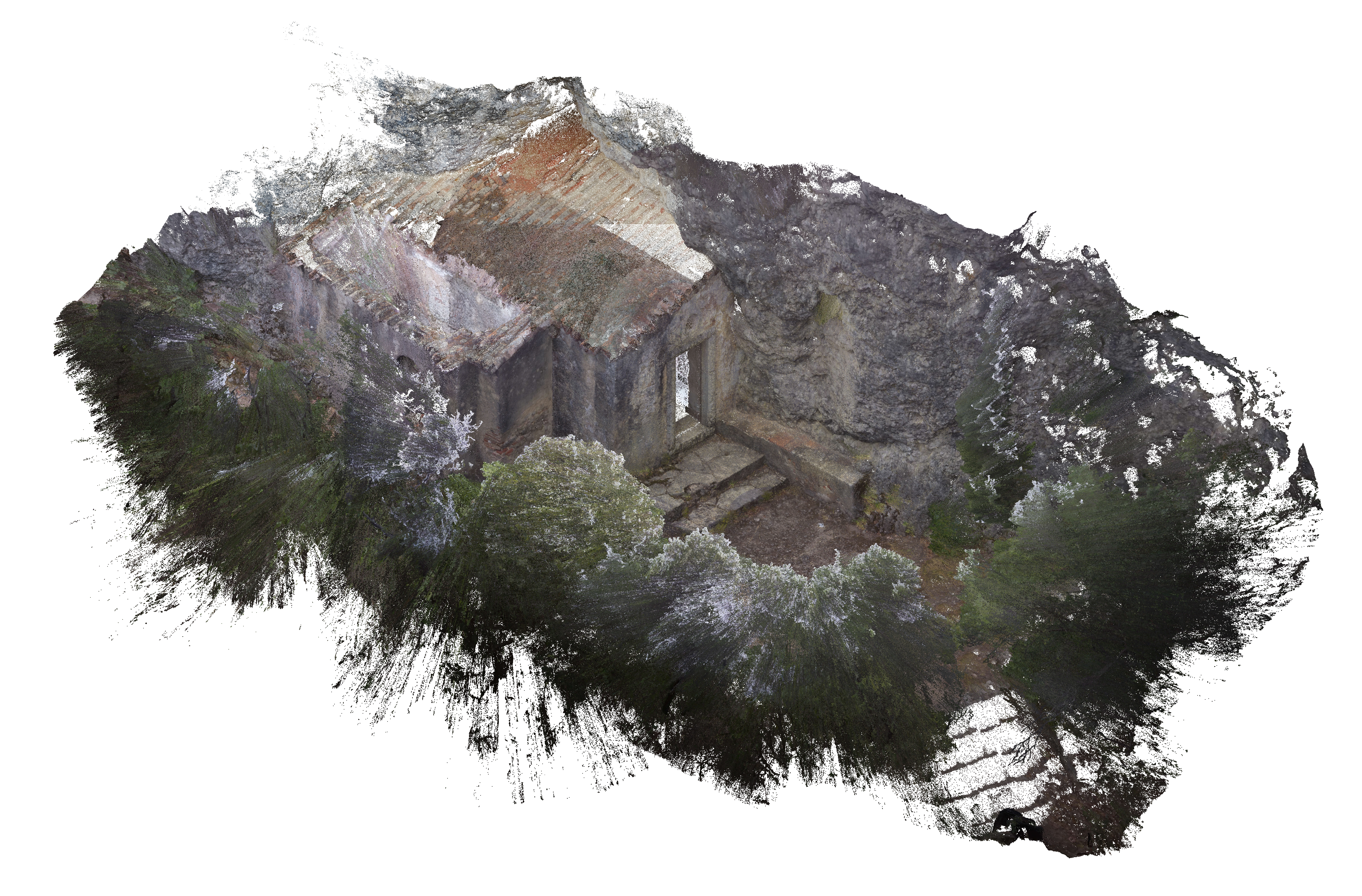

1) The Hermitage of Memory:

By Paulo Lopes and Tiago Moura

In 1215, a wealthy merchant or chaplain by the name of Hildebrant, left England in search of greater profits or religious pursuits, depending on which historic source one believes in. In either case he sold his possessions and sailed off toward Lisbon. One night a storm arose and threw the ship off course. Fearing for the crew’s life, Hildebrant ran to pray to the statue of Saint Mary kept onboard but couldn’t find it. As the crew prayed, a great flash appeared, turning night into day and tempering the storm. Guided by this light, they sailed safely to the coast of Arrábida and climbed the mountain where the lost statue of Mary was rediscovered. This inspired Hildebrant to build a hermitage in memory of the miracle where he promised to dedicate his life to loving and serving Nossa Senhora. Every year, the crew came back on pilgrimage to the Arrábida mountains.

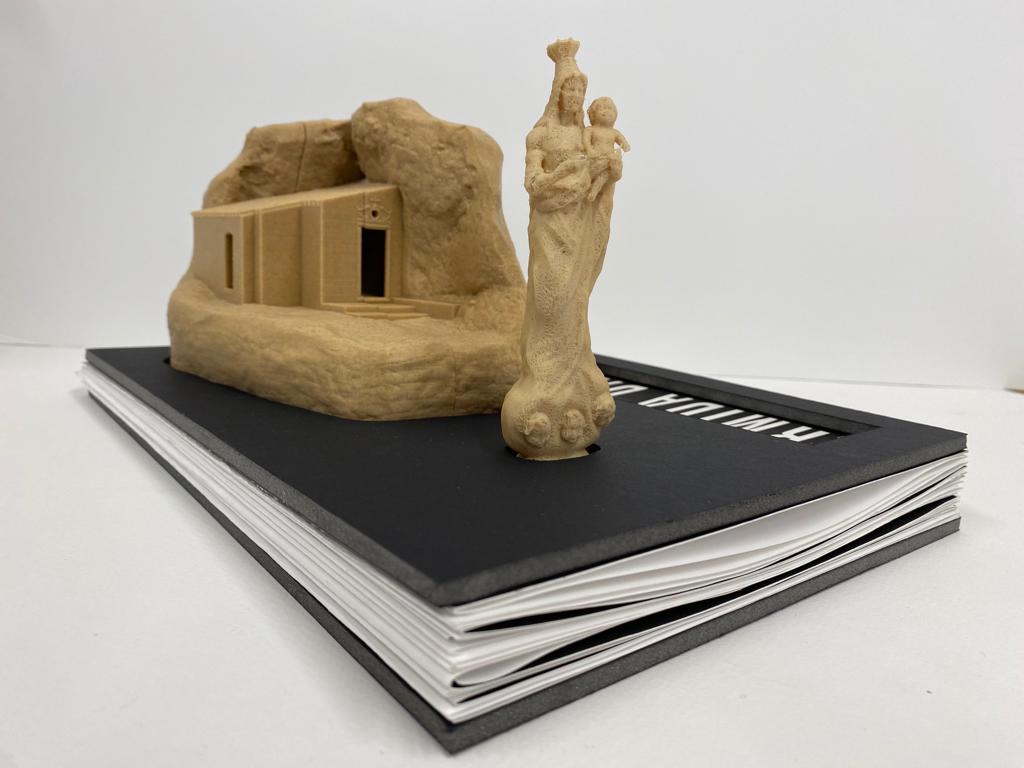

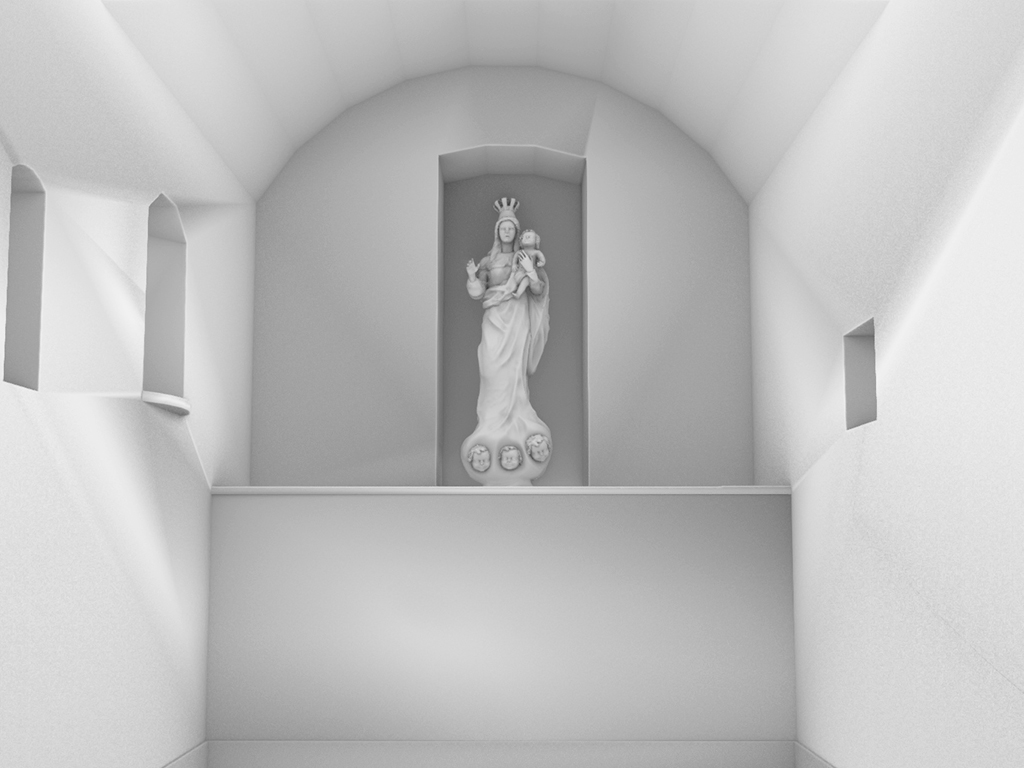

What remains today of this legend is the physical ruin of the hermitage built into the mountainside which inspired the original friars to settle their convent here over three centuries later. Because the space belongs to the old convent, located within the mountains, it is very rarely seen by the public. For this project, Paulo and Tiago used a combination of digital sculpting and HBIM modelling processes were used. Digital sculpting was explored to reconstruct the statue of Saint Mary based on photographic evidence of the last known statue housed within the hermitage. The hermitage itself was also modelled using a combination of laser scanning data to model the main building and photogrammetric survey data to create a digital mesh of the surrounding hillside as it truly exists. These two modeling processes were then merged in a 3D sculpting program, divided into two parts and finally 3D printed. The model provides a sense of physical accessibility to the convent through a scale model keeping the qualities and sense of the rugged terrain intact.

2) The Refectory and Kitchen:

By Paula Seifert and Robina Behrendt

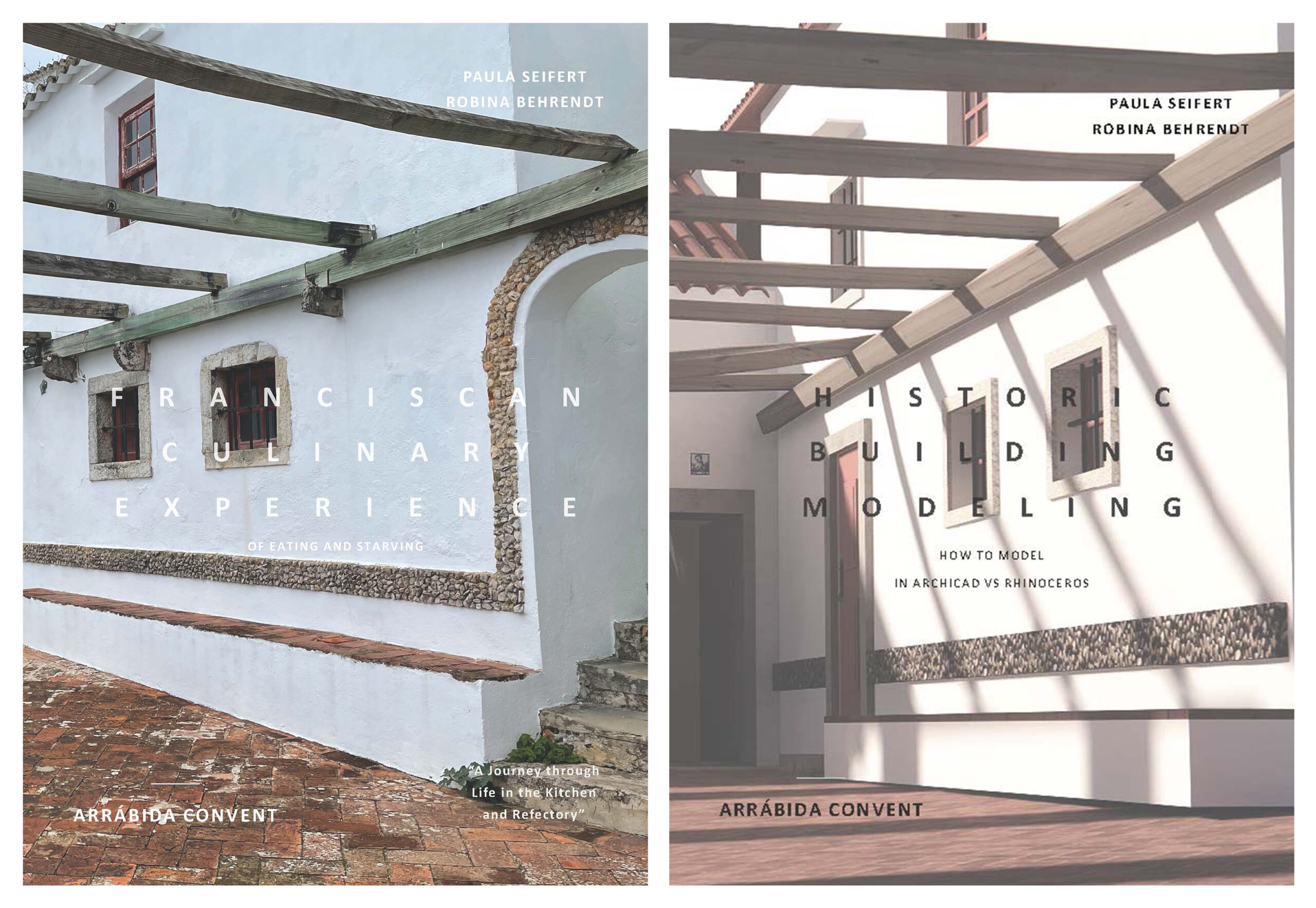

The kitchen and refectory are the spaces where the friars ate and prepared meals. They are built as two separate, but adjacent buildings joined by a small window to pass meals from the kitchen to the communal dining table. They are also joined by a central terrace in front, connecting to the chapter house and the dormitories. The buildings are in the direct centre of the new convent, marking them as an important axis of conventual life both spiritually through the enactment of communal rituals and physically through providing sustenance. The spaces are thus an ideal place for uncovering an ecological spirituality as it manifests in the everyday, mundane habits of life.

To communicate the research, the project was arranged as a cookbook which revealed the deliberate poverty of everyday life. Thus, in addition to a modelling project of these two buildings, the research explored the planation, water system, daily objects, dietary habits, table etiquette and religious symbols used within the architecture. Due to a sparsity of sources about the conventual diet in Arrábida specifically, and research on conventual diets broadly, the research was forced to rely heavily on speculations. These speculations were guided by an analysis of conventual rules as well as the physical evidence of food sources in the convent and surrounding mountains today. What is clear from these results is that the friars ate very little – getting by on fruits, vegetables, herbs and bread. The research relied upon previous studies to understand how the kitchen was fed water by a nearby fountain and how the excess water from the kitchen was subdivided between a large tank and a long gutter that supplied one of the vegetable garden tanks where the friars harvested edible and medicinal plants on the lowest level of the property. Some of the plants are still harvested there today. Overall, this was an important exercise in understanding how the architecture and landscape worked together to allow this self-sustaining community to function.

In addition, a separate modelling guidebook described several different modelling programs used in the project. This includes an evaluation of their different capabilities and limitations to model from point cloud data as well as exploring issues in the interoperability between modelling programs.

3) The Cell of Friar Agostinho:

By Maikel Hollstein

This theme aims to tell the story of the Frei Agostinho da Cruz, an Arrábida friar and well-known poet who spent his late life in the mountains of Arrábida. The cell that exists today was constructed in the old convent by the former guardian of the convent: Josef da Esperança, who in 1720 created a small house to memorialize the poet. Like Saint Francis, Frei Agostinho was remembered for his extreme asceticism, poverty and love of all creatures. He was often found speaking with birds or gardening. Controversially, he was also known for fishing, against the conventual rules. His works appeared in various forms: sonnets, elegies, ecologues, odes, songs, dirges and vilancetes. His poetry often expressed the conflict of between being human – as a sinner and yet longing for an ideal ascetic life and thus are a key to interpreting the difficulty and dedication required to live the “form-of-life.” This perspective is deeply embedded with his experience in the mountainous environment of Arrábida.

The cell was modelled in detail from the laser scanning and photogrammetry survey and inserted within a terrain model of the Serra da Arrábida. Afterward the project integrated atmospheric qualities like the clouds and mist famous of the area. The project even integrated models of some of the actual species of flora and fauna that inhabit the landscape. Here, digital applications were used to photograph and identify plant species during the site visit to create a compendium. All these diverse elements were finally combined and communicated with Twinmotion, a tool designed to create immersive animations and video experiences of modelled environments.

4) The Library and Cells:

By Izabela Gomes and Anna Chiba

The convent was overall a place of study, between the space of the library and individual sleeping cells. According to Giurgevich (2016), a conventual library acted as a “fluid library” or a “branched library” during this period. This means that the place where books were kept was not limited to the space of the library, as stipulated in the Estatutos da Província de Santa Maria da Arrábida. Instead, a library was any place in the Convent where a book could be found or read. In Arrábida, numerous types of literature could be found written by saints, priests, theologians, dogmatists, philosophers, historians, humanists. These were even combined with texts in the scientific, military and botanical fields, among others, signifying that convents in this period were some of the most important knowledge collections of their time. The collection, consisting of 2865 volumes, is today catalogued in the Online Catalog of the António Alçada Baptista Documentation Center, available for consultation. The books are being stored at Fundação Oriente, in the Fundo Livraria do Convento da Arrábida with restricted access by authorization. It is a rare example to survive the extinction of religious orders in Portugal in 1834 and provides significant knowledge about European conventual life of this period according to recent work documented by Ionel in A Livraria do Convento da Arrábida 1542-1834 (2019).

Taking these cues, the modelling project was developed as an interactive immersive environment to demonstrate a vision for a future virtual version of the collection where users could interact with books as they were originally arranged in the space of the convent. Staying true to the “fluid library” theme, Anna and Izabela also chose to model an example of a friar’s cell physically connected to the library where books could also be seen. Because the sleeping quarters also served as a mini-library, it was important to show a glimpse of how the friars lived and studied, in individual cells with a small table, bench and modest bed of cork.

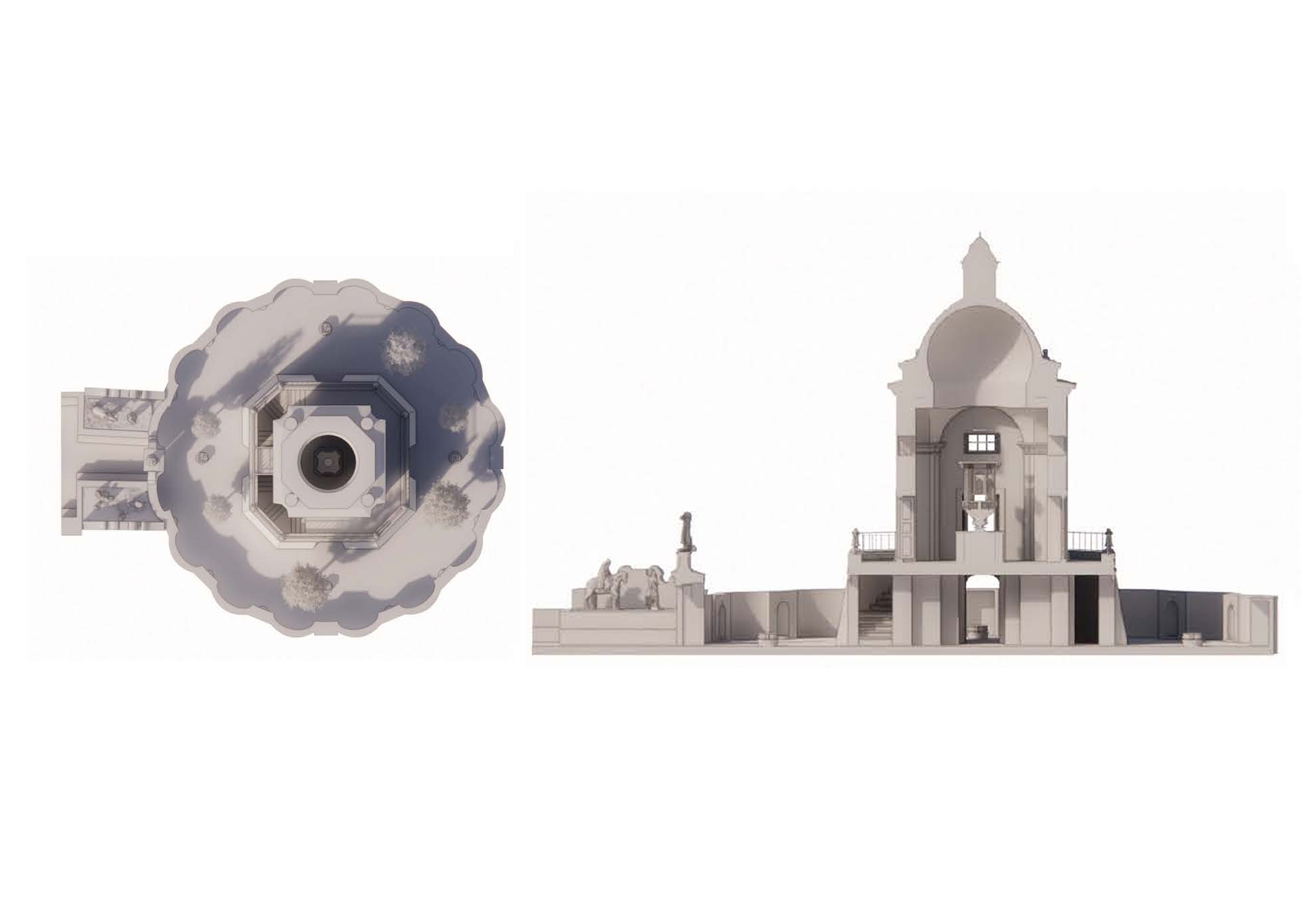

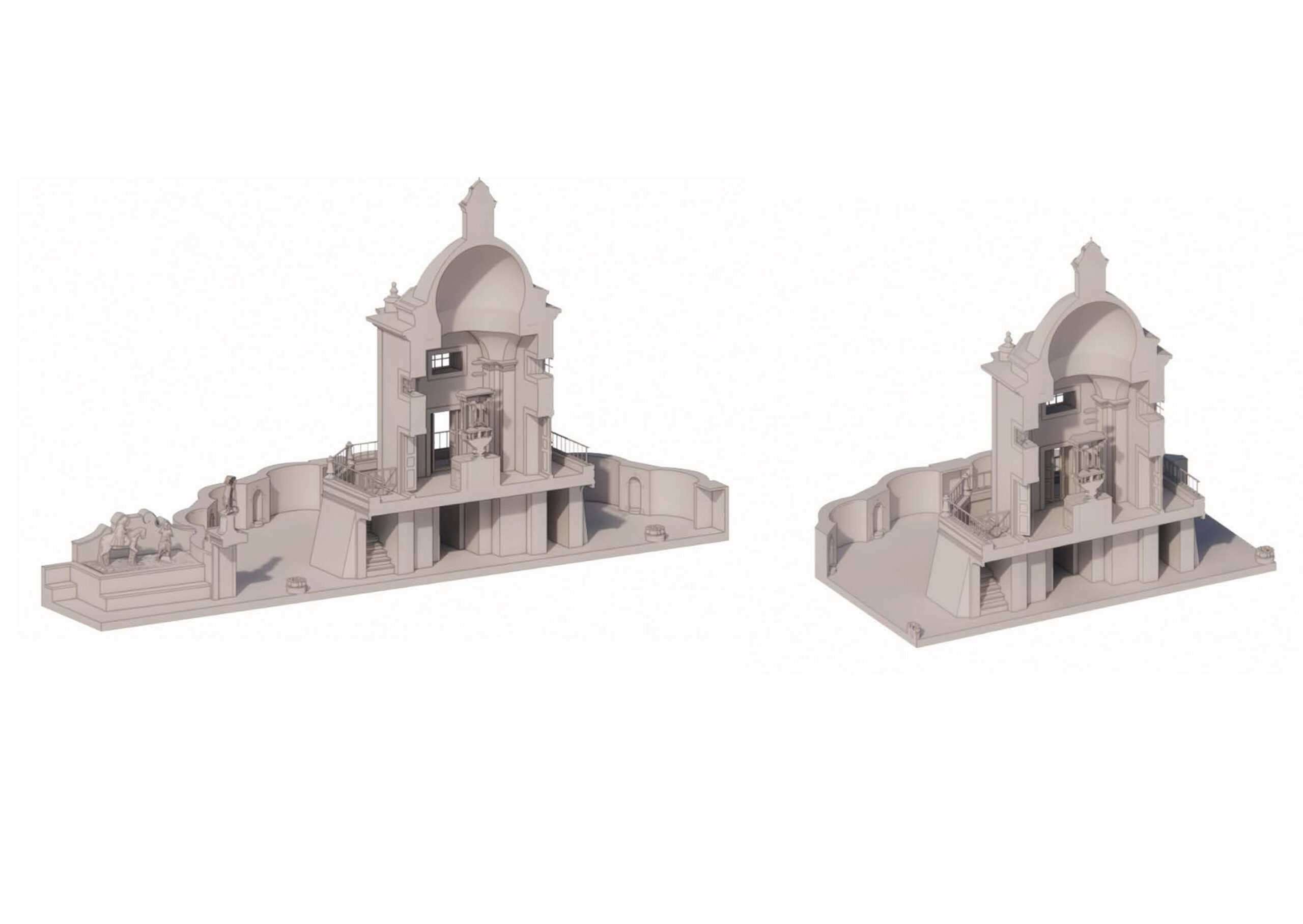

5) The Sanctuary of Bom Jesus:

By Leonor Antunes, Luís Campos de Azevedo and Rúben Coelho

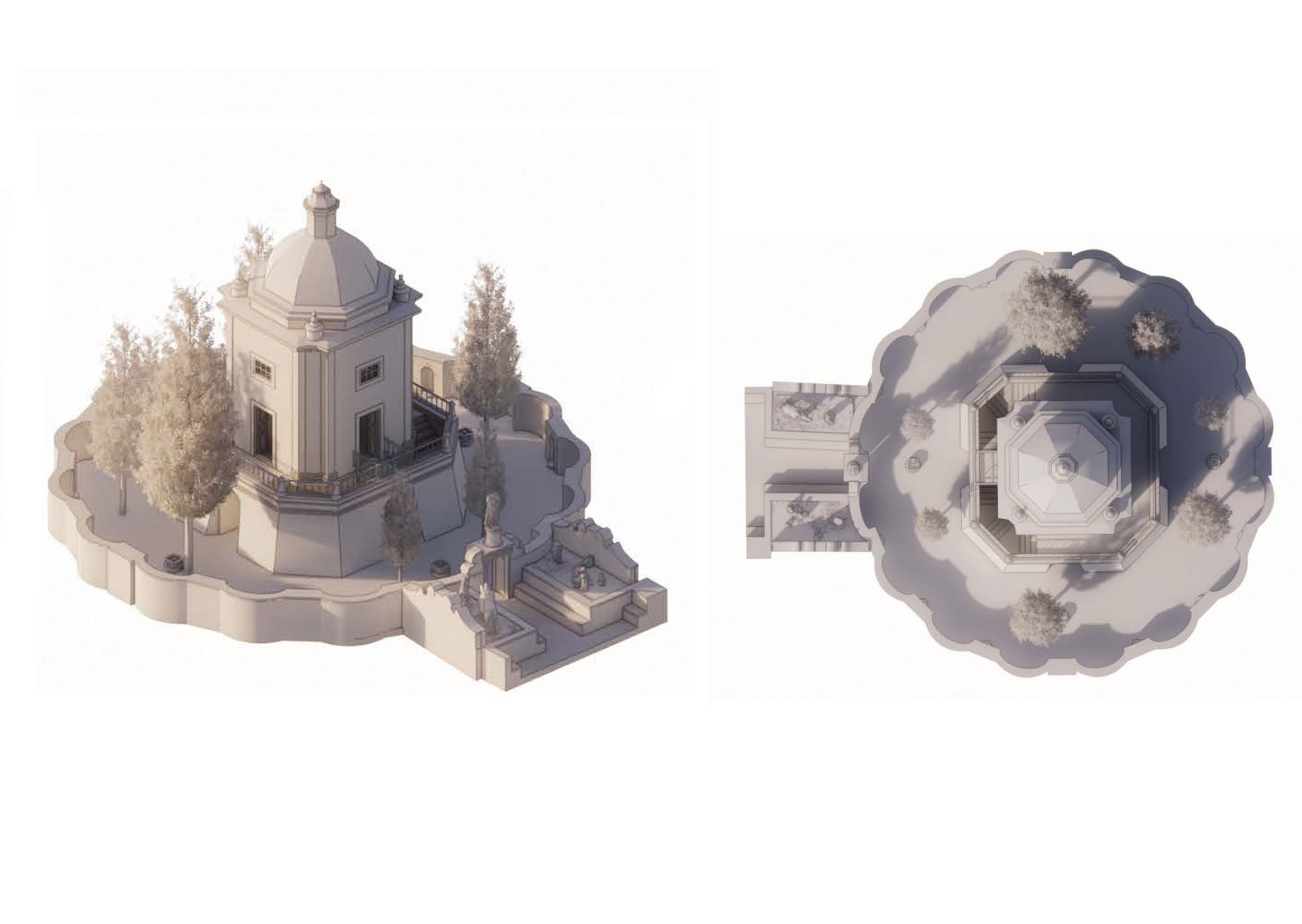

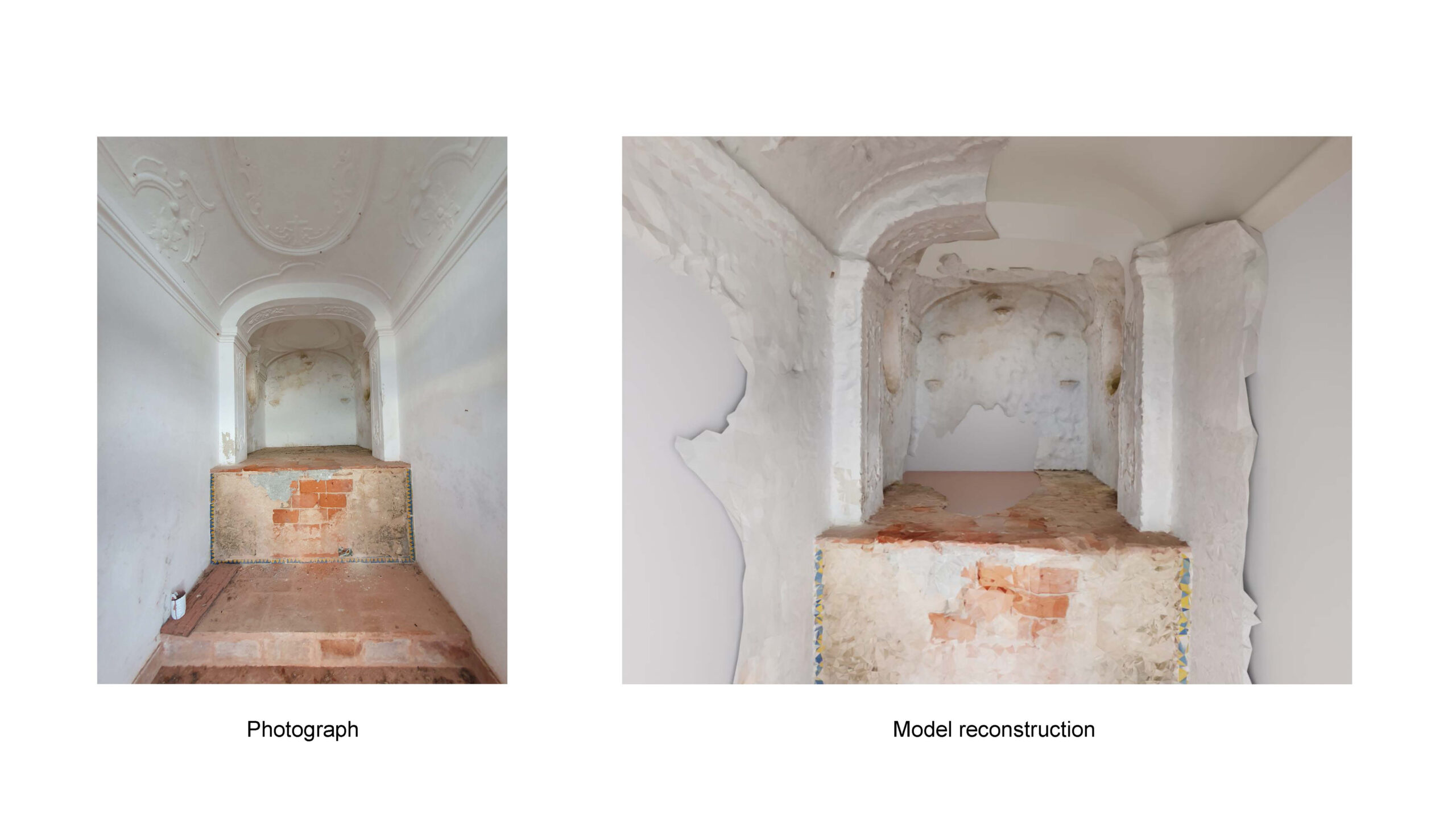

The building was erected in 1650 by D. Antonio de Lencastre the 15th, son of D. Alvaro. It was remodelled in 1729 as noted on the tiles at its entrance. Over the centuries it has faced vandalism, seen in the fragmented sculptures outside its entrance and its once elaborate gardens have faded over time due to a lack of adequate water sources in the present. A key to understanding the previous splendor of this space was the poetic description offered by Padre Inácio Monteiro in his “Descrição da Arrábida” (c.1685). The poem was written as a physical journey through the mountains and covers almost all the spaces across the old and new convent. Curiously, the author gives notable emphasis to the sanctuary of Bom Jesus over nine pages of text compared with the other spaces of the convent which are described only in two or three.

The digital model, built from point clouds and an HBIM methodology, was a way of deciphering these textual descriptions to imagine what the author was seeing in various scenes. A 2D portfolio combining disperse fragments and evidence from various texts, periods of history and representations provides a visual guide to interpret Padre Inácio Monteiro’s text. The role of the portfolio is to substantiate the poem with research bringing all known references of the sanctuary into one place. The final model of the existing condition of the building is communicated in an online QR code. An effort was made to reconstruct the whole of the Sanctuary of Bom Jesus, with emphasis on the Hermitage and the Inner Precinct. Studies of tiles were also included despite the scarcity of specific documentation for their accurate execution. Extensive work was carried out on the central altar.

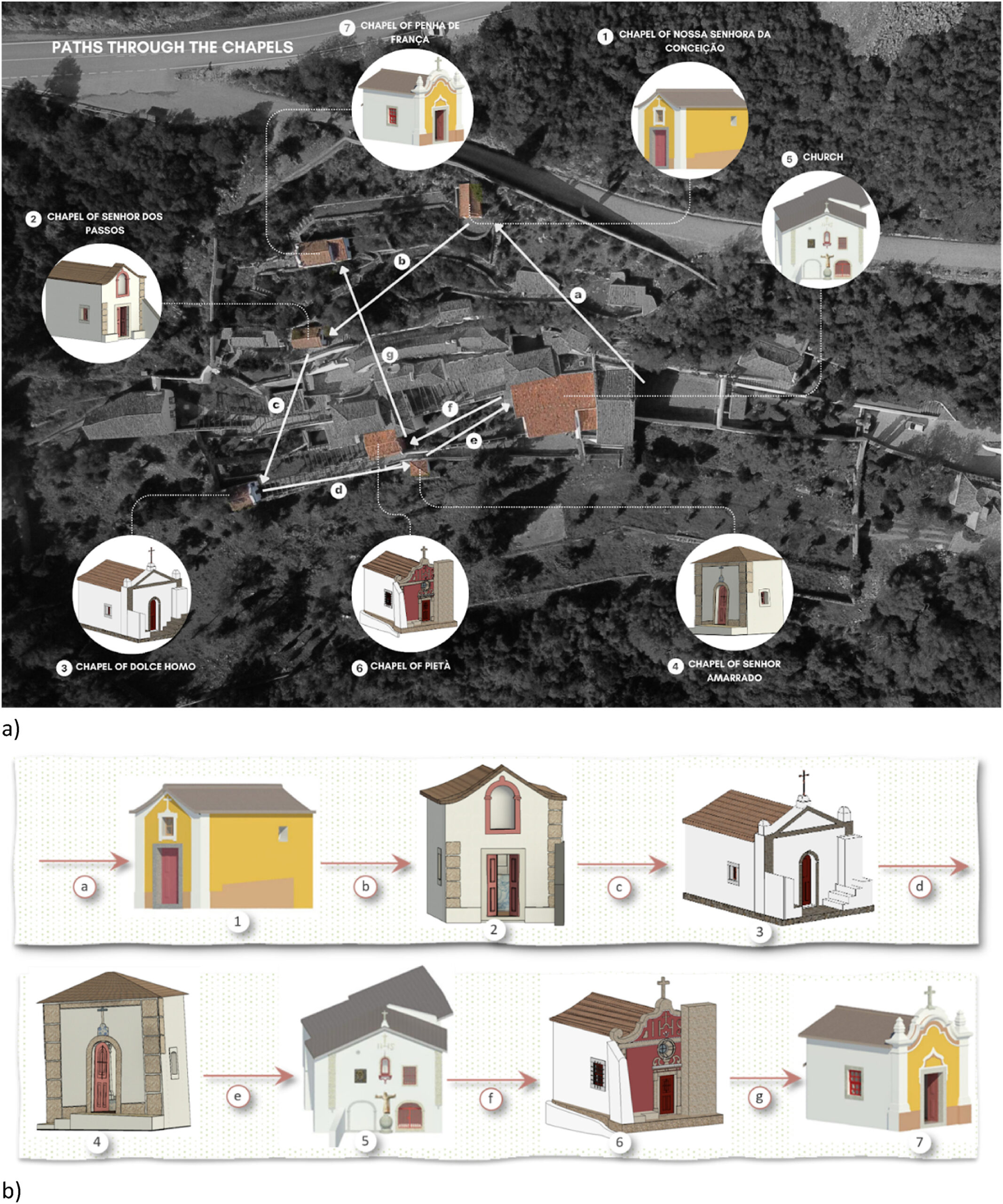

6) The Via Sacra Watchtowers and Chapels:

By Micaela Pais and Aljaž Gradišar

The via sacra, also known as “the way of the cross” or “the stations of the cross,” refers to the sequence of events that took place on the path that Jesus took carrying the cross from Pretorium to Calvary where he was crucified. The journey of the fourteen stations is commonly relived by religious communities as a pilgrimage for Christ’s suffering.

The main question of this virtual reconstruction project was how to retrace the intended via sacra in Arrábida, made up of unfinished and undocumented watchtowers in the old convent and a series of chapels in the new convent. The majority of these old convent edifices are today restricted to the public and little is known about how they functioned historically. The new convent chapels are publicly accessible, but little is known about their actual use. One thing that is clear is that the old convent portions have been left unfinished following their initial construction. Due to the lack of any historical data regarding the order of the stations according to building could not be assigned with certainty. From talks with Fundação Oriente, it was even gathered that the chapels of the new convent might have been added randomly without prearrangement. Thus, instead of using historic clues for this reconstruction, poems were used for each station to help value the sacrifice Jesus made whilst on the path to crucifixion. A 2D portfolio combined the imagery of the poems and models of the fourteen stations of the cross to speculatively reconstruct a path for the via sacra.

Since we did not have a complete digital survey, the old convent buildings were modelled primarily from a set of drawings made from an existing analogue survey done in 1998. Only two of the structures in the new convent had laser scanning and drone surveys. Thus, the project also explored digital surveying techniques from a hobbyist’s perspective to test the limit of available tools for low budget recordings. An attempt was thus made to document all of the remaining chapels of the new convent using photogrammetry to gather the data. A key part of this experiment was the use of affordable, non specialist equipment as well as open-source software to make the models.

Because of the involvement of students with the research, a large database of digital content was created. In all cases the student works combined sophisticated digital modelling processes with extensive historic research into the form-of-life of the conventual community. This included knowledge about local food sources, objects of daily life, plant and animal species, spiritual beliefs, literature, ritual practices, building techniques, and even an investigation into the use of water in the convent. An important requirement of the course was to communicate all the research into 2D portfolios and or online exhibitions to make this research openly accessible to the public.

The remaining spaces of the convent will be explored in future semesters of the Master of Architecture program at Instituto Superior Técnico Lisboa. Our future goal is that a holistic digital reconstruction project resulting from this work will contribute to a more systematic study and means of communicating the form-of-life of the convent.

What has been particularly fruitful from this semester is understanding the many possible directions for public engagement offered by digital tools from physical models to online virtual experiences. In particular, we have identified the capacity of digital tools to make inaccessible spaces such as the Old Convent, accessible again. By reconstructing these spaces, the public could be given access to otherwise inaccessible spaces to better understand the asceticism of the earliest from-of-life in Arrábida. Today the old convent is unfortunately largely overlooked, even though it was the birthplace for significant Franciscan conventual communities in the country such as the Capuchos convent in Sintra and the famous National Palace of Mafra, both designated as UNESCO world heritage sites. One of the primary reasons for this is that the mountainous terrain prevents physical public access, the spaces are in a high state of degradation, and due to climate change factors, are now located within a forest fire risk zone during the summer months.

To make our vision possible, we have discovered the need to explore long term accessibility solutions for virtual environments, such as those currently offered by video game engines. This semester has shown the limitations of several open-source options for hosting digital modelling content. Though they provide a means of access, they are unable to create extensive customisable educational experiences for heritage. They can also come with large monthly operating costs which impede the long-term accessibility of digital content. By creating an online immersive experience through video game engines, the project could for the first time allow public access to vestiges of the convent which are currently inaccessible due to public safety measures. Thus, future research efforts will aim to investigate these tools to provide the public with an enhanced understanding of the importance of the architectural, geographical, and cultural landscape of the region by experiencing it firsthand.

Acknowledgements to:

Fundação Oriente

Instituto Superior Técnico – University of Lisbon

Tokyo College – The University of Tokyo