Digital Betrayals: “Translating” the Ancient Drawings of the Monastery of Nossa Senhora da Rosa

Damiano Aiello a, Jesse Rafeiro b, Ana Tomé c

a Carleton Immersive Media Studio, Carleton University, 1125 Colonel by Drive Ottawa, Canada

b Tokyo College, The University of Tokyo Institutes for Advanced Study, The University of Tokyo, Hongo,113-8654 Tokyo, Japan

c Civil Engineering Research and Innovation for Sustainability (CERIS), Department of Civil Engineering, Architecture and Environment (DECivil), Instituto Superior Técnico, Universidade de Lisboa, Av. Rovisco Pais 1, 1049-001, Lisboa, Portugal

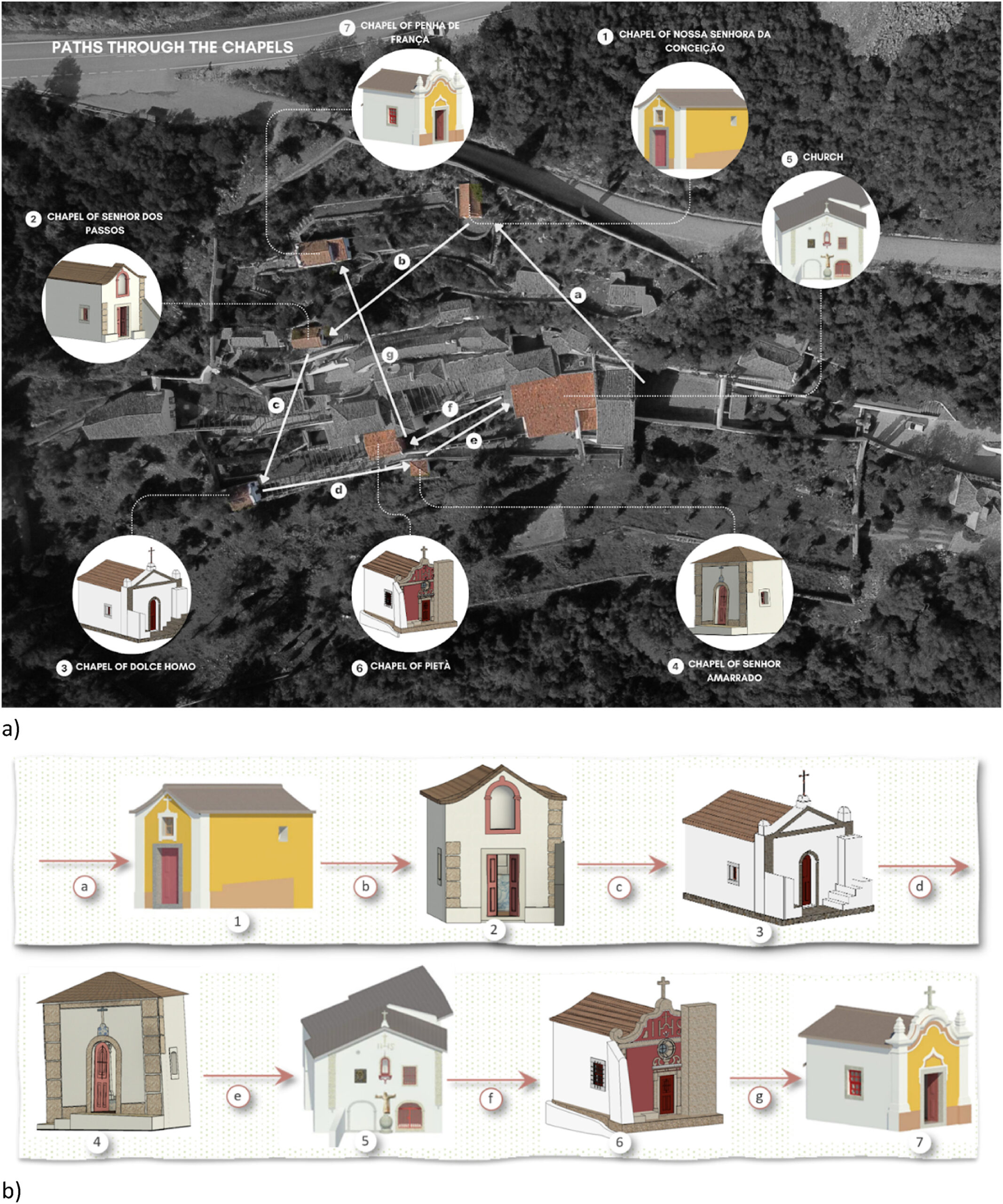

This paper investigates the ethical and philosophical implications related to the analysis and interpretation of historical sources of cultural heritage through the use of digital technologies. The latter are not neutral tools; rather, they actively shape heritage narratives, influencing how we perceive and represent the past. As such, the reconstruction of the past through heritage fragments cannot be objective or universally accepted, as it is inherently shaped by contemporary social, cultural, and political contexts. The past, therefore, can only be analysed from the unique perspective of the present. In this regard, the American historian David Lowenthal suggests “the past is a foreign country,” and therefore, its language, customs, and traditions cannot be fully understood. Since heritage is irreconcilable with the past, or more precisely —quoting Lowenthal again — since heritage is a “distortion” of the past, cultural heritage studies should combat those simulacra that define the past as objective, unambiguous, and unquestionable — definitions that academia often protects. Taking the Monastery of Nossa Senhora da Rosa of the Order of São Paulo da Serra de Ossa (Caparica, Portugal) as a case study, this paper represents an opportunity to reflect on the ambiguity implicit in the reading of historical sources, which always involves a certain interpretive and creative component. Borrowing the semiotic concept of translation, it is possible to say that reading any source is comparable to translating a document from an obscure and mysterious language, that of the past, to the contemporary world language. However, during the process of transferring the meaning of words from one language to another, many nuances inevitably end up being twisted, lost, or otherwise altered. Consequently, “translating” the drawing into the real building (as well as into a virtual replica) is, to use a famous analogy dating back to the 16th century, a sort of “betrayal,” a departure from the initial idea represented on the sheet. This is particularly pertinent when the artefact no longer exists, as is the case with the Monastery of Nossa Senhora da Rosa. What are the limits of interpretation, its criteria, and the freedom that the “reader/interpreter” can take? What is the role of digital technologies in this theoretical framework? This research, rather than extolling the photorealistic results of digital heritage visualisations and their uniqueness, focuses on the process that led to certain interpretations, emphasising their subjective and context-dependent aspects.

Virtual Archaeology Review 17(34)

https://polipapers.upv.es/index.php/var/article/view/23394